One Saturday in mid-September I spent a morning in the Royal Mile in Edinburgh. No: not for that. I was there for a guided walk: a risky undertaking, I thought, from several points of view. The walk was to start in Dunbar’s Close Gardens, a 16th century ‘close’ in the Canongate part of the Royal Mile (something like two thirds of the way down towards Holyrood) and scheduled to finish two hours later, in the New Town. The subject was Patrick Geddes and his influence on the development of gardens. How was I going to keep up? Then there was the weather. And the people in the streets. The buskers and the jugglers and the drifters and the coaches depositing tourists and picking them up. And then there was my botanical ignorance. At the same time, I was curious, because I didn’t associate gardens with the Old Town. A palace, a castle, and a parliament; whisky shops; pipers; fudge, and Scottish cashmere manufactured anywhere but Scotland, yes; but gardens?

It’s not exactly true to say that Geddes is an invisible presence in the Old Town. There is at least one commemorative bust, in addition to the centre dedicated to him (of which see more below). But I think it’s fair to say of all the beautiful and remarkable things there are to see in and around the Royal Mile, you don’t expect to come across the work of a modern visionary.

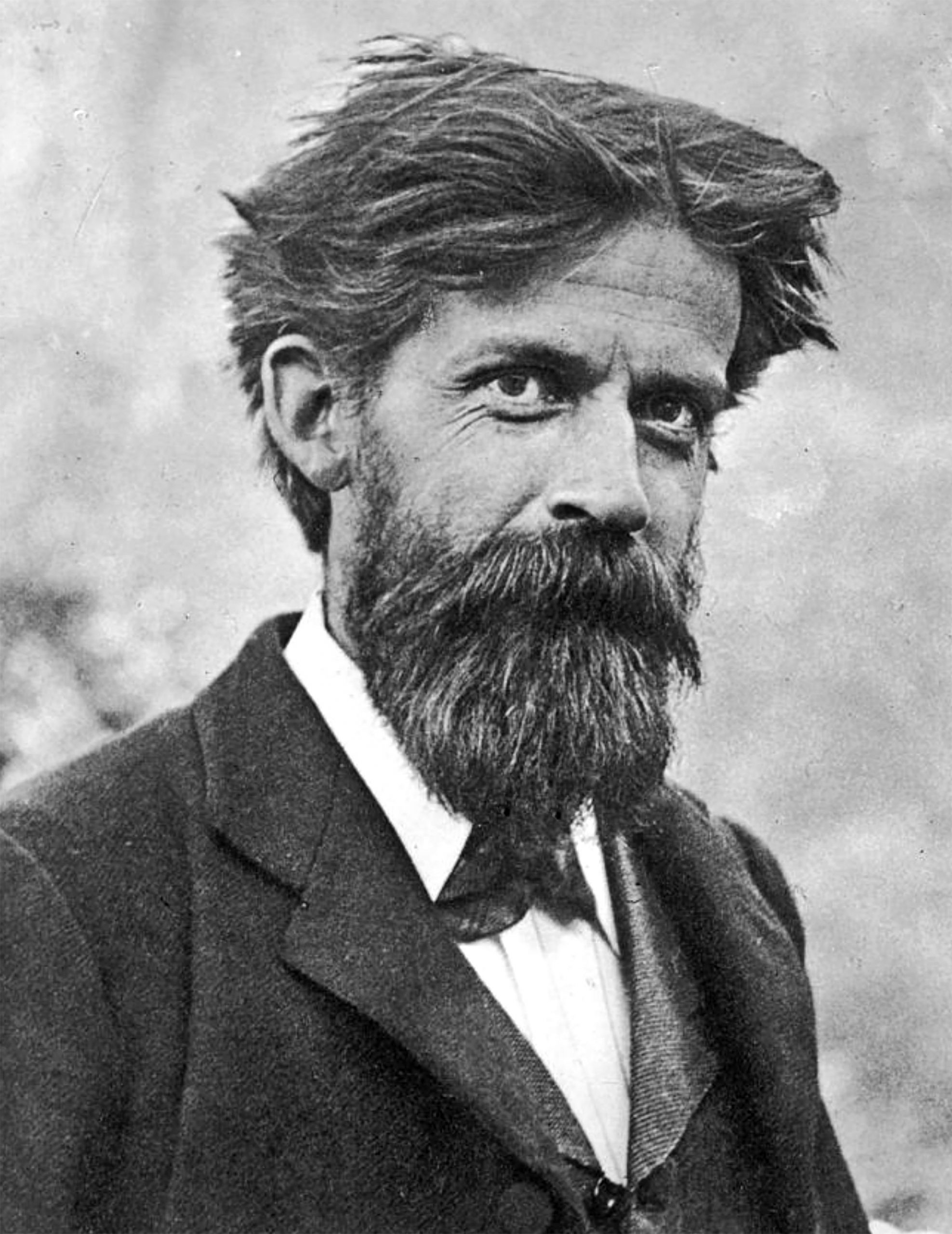

The guide, a lively woman called Claudia, had been provided with a microphone, and fortunately most of the time she remembered to use it. Together with a photo of Patrick Geddes fixed on a stick, held in one hand, and a sunflower flourished in the other, she planned to keep the group together. She revealed herself as both a fan and a student of Geddes, and is currently completing a PhD on his influence on the practice of art. The walk had been arranged by a charity called the ‘Moray Feu’, made up of owners and residents who live in the splendid Moray Place in the New Town. Their gardens are private (in fact, finding the gates open, we’d recently ventured in with a friend, only to be instantly identified as non key-holders and shown out) but to celebrate their bicentenary in 2022 their committee devised a series of events open to the public. The Patrick Geddes walk, though nothing to do with the New Town, was one of these.

Patrick Geddes was born in Ballater, Aberdeenshire, in 1854, the son of a former soldier, Alexander Geddes. He grew up in Perthshire. ‘I grew up in a garden,’ he said of his childhood. The family was Jewish in origin, but more influenced by the Free Church of Scotland than Judaism. Geddes was intellectually gifted but his formal education was fitful and diverse. He soon abandoned study at Edinburgh University and then studied at the Royal College of Mines in London under Sir Thomas Huxley. In due course he became a Professor of Botany at Dundee University, but according to the National Library of Scotland, Geddes hated exams and never took a degree. His first post in Edinburgh was as an Assistant in Practical Botany. From the start Geddes’ interests were wide-ranging. Study of Auguste Comte led him to develop ideas of positivism and the belief that human society could be improved, if not perfected. He was never a specialist: in fact he deplored specialism, seeing it as a hindrance to social progress. His ideas on town and city planning were to become hugely influential, but he came to be seen as a much broader figure, anticipating the disciplines of economics and sociology as well as environmentalism. He began from the simple but radical premise that the urban environment should be designed for the benefit of everyone. He created an impressive design for Perth which was never implemented, but which influenced work he did in India and Palestine, and notably in designing the modern city of Tel Aviv. He helped found the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He was also a Francophile, and eventually retired to Montpellier, where he died in 1932.

Dunbar’s Close gardens

Geddes’ wealth came from his wife, Anna Morton, the daughter of a Liverpool merchant. By the mid nineteenth century much of the housing in the Old Town was insanitary and overcrowded, those residents with the means to do so having moved long ago to the New Town or to the Edinburgh suburbs. Geddes believed that in order to improve an environment you needed to immerse yourself in it, and in the 1880s he moved his wife, then pregnant, from a home in Princes Street to what was effectively a slum in James Court in the Royal Mile. By example, encouragement and the exploitation of contacts he initiated a scheme of environmental and housing improvement. He planned 75 gardens, of which only ten were realised, but also encouraged community gardening and the growing of edible plants in the city centre. We saw examples of tiny community gardens still flourishing today in the spaces cleared in what had been dark, densely populated tenements behind the facades of the Royal Mile. Dunbar’s Close Gardens was planted on the site of a derelict court: a garden of four ‘rooms’ to illustrate growth and colour throughout the seasons.

Geddes and his wife developed the derelict James Court into one of the earliest halls of dedicated student accommodation outside the collegiate model. He set up the first dedicated hall of residence for female students. He helped establish a primary school, just below the castle at the top of the Old Town. Here, while children spent the mornings studying the (relatively limited) curriculum of the time, they spent their afternoons in the adjacent garden, learning about nature. He promoted the restoration of Riddle’s Court, a 16th century close, setting up a self-governing student residence there, and holding between 1883 and 1903 a series of summer schools which attracted teachers and scholars from all over the world. He also pioneered adult education, believing that education should be life long: ‘through living we learn’.

Riddle’s Court

Sculptured Leaves

in Riddle’s Court

The Patrick Geddes Centre has been established in this beautiful restored court and in the pavement is a sculpture of leaves, to commemorate one of Geddes’ mottos, taken up by contemporary environmentalists: ‘by leaves we live’. In a farewell lecture at Dundee University in 1919 Geddes explained what he meant by the phrase:

“By leaves we live. Some people have strange ideas that they live by money. They think energy is generated by the circulation of coins. But the world is mainly a vast leaf-colony, growing on and forming a leafy soil, not a mere mineral mass: and we live not by the jingling of our coins, but by the fullness of our harvests.”

He also said:

“How many people think twice about a leaf? Yet the leaf is the chief product and phenomenon of Life: this is a green world, with animals comparatively few and small, and all dependent upon the leaves.”

Just below the castle, at the top of what became the Geddes’ family home, is the Outlook Tower, converted by Geddes from a former observatory and used by him as a ‘sociological laboratory’, to illustrate another maxim, a phrase which Claudia attributed to him: ‘Think global, act local’. Exhibitions on successive floors encouraged people to focus on their immediate environment and gradually expand their perspective, to take in the world as a whole and appreciate their place in it.

I felt a great rush of optimism and delight in the course of this walk. Optimism that so many of these ideas are still current (if still aspirational) and delight that this extraordinary figure was part of Edinburgh.

But there were sadder reflections, too.

At various points on the walk Claudia waved the stick and interrogated Patrick Geddes’ photo. What do you think of this, Patrick? What do you think of Riddle’s Court being closed to the public and used as a wedding venue? What do you think of the building where you used to live, where two thirds of the apartments are Air BnB, as are so many in the Old Town? Why is the garden to the primary school locked? What do you think of the use of the Outlook Tower, your environmental laboratory, as a tourist attraction?

I wonder what Geddes would make of the Old Town as a whole: part Disneyland; part royal, military and political bastion; part architectural marvel. Poverty, like wealth, has become more complex and disparate in Edinburgh than it was in the 1880s. You might not find it now in the ‘closes’ of the Old Town, but its contemporary equivalents are not far away.

On the Patrick Geddes page on the National Library of Scotland’s site I read: ‘Patrick Geddes is known more for his magnificent failures than his successes. He was disorganised [and] had difficulty in disciplining himself to write for publication. He seemed to be unable to complete tasks and to collaborate effectively. He flitted like a butterfly from one topic to another. And he must have been infuriating to work with. He was called ‘a most unsettling person’.

It was a relief to discover that Geddes had weaknesses. And who wouldn’t give a lot to be remembered for even a single magnificent failure?

Since the Geddes walk I’ve come across positive evidence of Geddes’ collaborative skills, as well as evidence of how widely his influence was felt in the intellectual life of his time. For several decades Geddes was a close associate of Dr Arthur Brock (1879-1947) the physician who treated Wilfred Owen and other officers for shell shock and neurasthenia, at Craiglockhart War Hospital during World War I. Brock’s own ideas ranged widely and deeply, encompassing ancient Greek medicine and its potential for current medical theory and practice, as well as theories on the future of society as a whole. Brock was preoccupied with the challenges and opportunities of modernism as he saw them, and became associated with a form of Scottish nationalism.

David Cantor’s article: ‘Between Galen, Geddes, and the Gael: Arthur Brock, Modernity, and Medical Humanism in Early-Twentieth-Century Scotland’ asserts that Geddes was a key influence in developing many of Brock’s ideas. Brock was impressed by Geddes’ contention that mass migration to the cities as a result of the industrial revolution had ruptured what he called the ‘evolutionary equilibrium’, destroying the basic connection of place-work-folk which Geddes placed at the heart of a properly functioning society. The way that urban living had subsequently developed (let alone the horrors of war) had done nothing to mend this. In fact Brock regarded neurasthenia as a manifestation of this breakdown in its most extreme form. Brock became actively engaged in encouraging patients, and people more widely, to explore and assess their own immediate environments, as a means to recovery, and as a way to begin improving their lives. Brock’s treatment of Wilfred Owen, which included a programme of exploration and assessment of Edinburgh, was an example of this approach. When Geddes was abroad Brock took over work at the Outlook Tower, Geddes’ sociological laboratory, and he also organised visits to the Pentland hills and other sites to study different types of environment.

In his article David Cantor quotes from a handwritten note (unattributed) from the Siegfried Sassoon papers held in the Imperial War Museum, giving a vivid picture of Brock in action: ‘Very tall, thin, hunched up shoulders, big blue hands, very chilly looking, with a long peaked nose that should have had a drip at the point. High pitched voice suggestive of Arctic regions. Full of energy. Pushed his patients out of bed in the dark cold mornings & marched them out for a walk before breakfast.’

The sun shone all morning on that September Saturday, and we reached the end of the walk in Moray Place Gardens exactly on schedule. This time we weren’t thrown out, but allowed to admire the sweep of its lawns and the sense of being in the centre of parkland while at the heart of the city. Moray Place is all about beauty and proportion. Patrick Geddes had no involvement in the later development of the New Town. In fact his work in the city began as a kind of reaction, or riposte to it; and if he had any connection with Moray Place it was probably a social one. But in future I shall always think of him as linking Edinburgh, old and new; rich and poor, with an Edinburgh he helped to reimagine.

‘Between Galen, Geddes, and the Gael: Arthur Brock, Modernity, and Medical Humanism in Early-Twentieth-Century Scotland’ Article by David Cantor, published by Oxford University Press in The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, January 2005, Vol 60, No 1 (January 2005), pp 1-41

Other sources of information:

The Patrick Geddes Centre: patrickgeddescentre.org.uk

For Riddle’s Court – Scottish Historic Buildings Trust – shbt.org.uk

The National Library of Scotland – nls.uk search for Patrick Geddes

Thank you, Heather: a greatly enjoyable account of a fruitful morning. I knew nothing about Patrick Geddes before. So many of his thoughts and principles for a good life are still ours, familiar and uplifting even if, like him, we haven’t achieved them yet. To live by the fullness of our harvests not the jingling of our coins is truly something to aim for. Perhaps Edinburgh could start by unlocking the gate to the primary school garden and reopening Riddle’s Court.

Thank you Sally. I’m pleased I conveyed some of the excitement the walk generated for me. I too was very struck by Geddes’ words about leaves and harvests, and look forward to reading more of the words he did manage to record.

What an interesting character..someone who would go the extra mile! Thank you for the article..if it wasn’t for you I’d never have known about him…there must be others like me!!

Thank-you Heather really enjoyed the article- read it twice, so interesting…I so admire folk like him who go the extra mile!