Spell Songs is a development from The Lost Words, produced by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris in 2017. (www.thelostwords.org) The Lost Words took twenty common names for twenty common species of plant and creature, chosen because the authors felt they were on the point of disappearing, as Macfarlane puts it: ‘from our stories, minds, dictionaries and habitats’. Macfarlane composed a ‘spell-poem’ for each of these words, in an act of reclaiming or ‘summoning-back’ as he calls it, into the culture. Jackie Morris created illustrations to show the stages of this magical, imagined reclamation.

The Lost Words hit a nerve: it became itself, in the words of its creator, ‘a wild creature’ widely read and used alike in schools, care homes and hospices across the UK, both with people who have yet to form their vocabularies, and with those who have lost them, through illness, trauma, displacement or dementia.

Spell Songs takes each of these spells and forms them into songs which were created and recorded by a group of eight songwriters, musicians and performers, who gathered with Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris to create and work on ideas. The songs were produced and recorded in the early months of 2019.

In his introduction Macfarlane states: ‘We are presently living through an age of loss, for which we are only just starting to find the language of grief. Disappearance — of language, species, loved places, loved people — is the tune of our times.’

This statement was, of course, about the present moment, in spring 2019. Now it also seems tragically prescient.

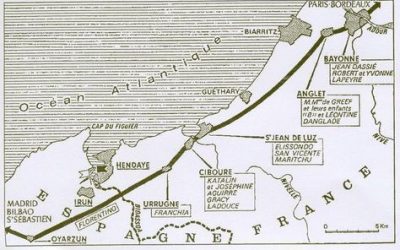

In part you could argue that his statement merely reflects the consequences of human mortality. Certainly it has been relevant for at least two centuries. It’s the story of the modern world of industrialisation and consumption, only now taken to an extreme point where the long term survival of the earth itself is threatened. Seckou Keita, kora player and ‘griot’ (praise singer) from Senegal, one of the collaborators on Spell Songs, writes about the impact of Zircon mining in the Casamance region of Senegal. Zircon is a mineral found in sand, and is used in the production of mobile phones. Zircon mining in the region means that hundreds of acres of coastal environment and dune networks, together with the birds, animals and plants who depend on these habitats, will be destroyed. What are the chances, given the demands of modern societies, of preventing this?

Suddenly (it seemed) in 2020, the Covid 19 pandemic showed everyone, including those who had been reluctant to take on the implications of habitat destruction and global warming, that human beings are part of the natural world, and like other living things are subject to forces they cannot understand or control. When the pandemic is past, what will happen? Will humans become even more self-centred than they were before, even more intent on furious consumption, trying to make up for lost time? Or will we take this opportunity of a long moment to reconsider, and even to change?

Heartwood is one of the spells in Spell Songs. Robert Macfarlane writes the spell in the form of the spiral of a tree’s trunk, the tree itself making a plea to the tree cutter against its own destruction. ‘I am a world, cutter,’ the tree protests. ‘I am a maker of life’. Karine Polwart takes some of the same words to set the plea to music. ‘Would you hew me to the heartwood, cutter?/Would you lay me low beneath your feet?’ Always one to urge the complexity of an issue, Karine Polwart points out in a note that the spell is one against unnecessary destruction, and that wood cutters are some of the best-informed people about trees when they do need to come down. Living is a practical business. Trees, in so many ways, and for so long, have been part of that practical business.

But they can also offer a corrective to a human-centred view of life. In his poem ‘Nature Notes’, published in his collection ‘It’s About Time’ Malcolm Cooke puts the tree at the centre of time and history. (https://malcooke.com/nature-notes-by-malcolm-cooke/)

He starts with the book, arguably the richest as well as most creative use humanity has made of trees. There are books, and there are words; but ‘tree’ is more than these. To the tree human beings are ‘… like the breeze/skipping over the world./You are here/and then you are gone;/a sometime sparkle of light.’ The song of the earth runs through the tree’s core. There is religious imagery in the poem, but it’s not the imagery of any specific religion. The tree is beyond human understanding, but we should know enough, by now, not to threaten its existence.

I like very much your exploration of how these interwoven themes have been captured and reflected in diverse ways through writing, illustration and music.