One publisher commenting on my manuscript observed that its title – Heartwood – was potentially misleading, suggesting a romantic love story. Heartwood is a story of love – and loss – but it is essentially a story of survival. Heartwood itself is the very opposite of a soft, romantic substance. It’s the hardest wood at the centre of the tree because although it doesn’t decay, it’s no longer living. Provided the outer layers of the tree: the bark; the phloem, the layer of living cells which transport food around the tree, and the largest part of the trunk, composed of both sapwood and heartwood (xylem) – are intact, the heartwood remains strong. The sound of the French word for heartwood, derived from the Latin: ‘duramen’ perhaps gives more of the idea. It doesn’t shrink; it has a deeper colour than the rest of the wood, and it is extremely strong. For these reasons, over the centuries, it has been the preferred choice for furniture making.

My novel’s protagonist, Irène, exemplifies some of the qualities of heartwood. She survives deportation and the death camp partly by chance, and partly because of her inner strength and resilience and a determination not to respond to people around her. This attitude – a kind of hard passivity – stays with her in her postwar life, and although her core attachments remain very strong, she is in many ways unable to grow or to understand growth and change in society around her. Although she feels she belongs to the 12th, and certainly to Paris, she’s not a furniture maker. In pre- and postwar Paris it was not possible for women to train to become woodworkers, let alone ‘ébénistes’, the designer-craftsmen and specialists in marquetry who had formed the élite of the artisan community from the days of Louis XIV. Instead she is largely self-taught as an upholsterer. Ironically, perhaps, in view of her solitary ways and social awkwardness, her work is about making things presentable and comfortable, disguising imperfections and creating furniture for everyday enjoyment.

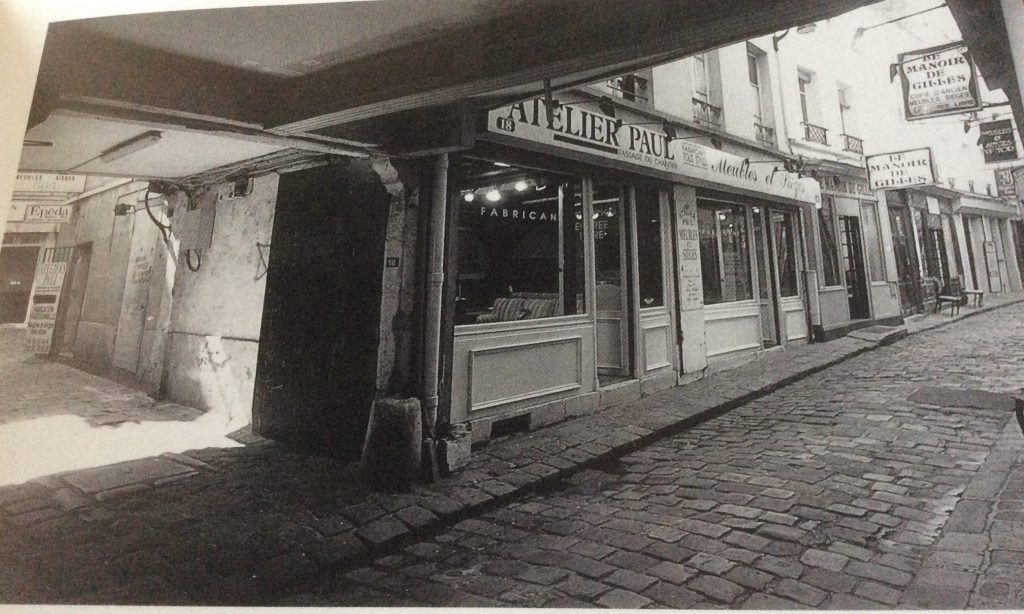

The making of furniture was central to the life of the 12th arrondissement from the 17th century, partly because of ease of access to the Seine, where timber could be transported by barge and uploaded directly to the centre of Paris. By 1930 there were still some five thousand ‘ébénos’ living and working between Bastille and Nation, alongside many thousands of more humble artisans in the form of apprentices, labourers, and upholsterers; as well as those who marketed and sold furniture, or ran the myriad small shops and workshops supplying tools and other essentials of the trade. Following the second world war came ‘les trentes glorieuses’, three decades of modernisation and prosperity for France (though not, of course, for everyone). In the 12th the traditional trade in furniture making gave way to an ever expanding mass market of machine-made products, made of new, cheaper materials. Thousands of skilled jobs disappeared. Even the least pretentious of the traditional designer craftsmen moved away from the world of the artisan and closer to the world of the artist.

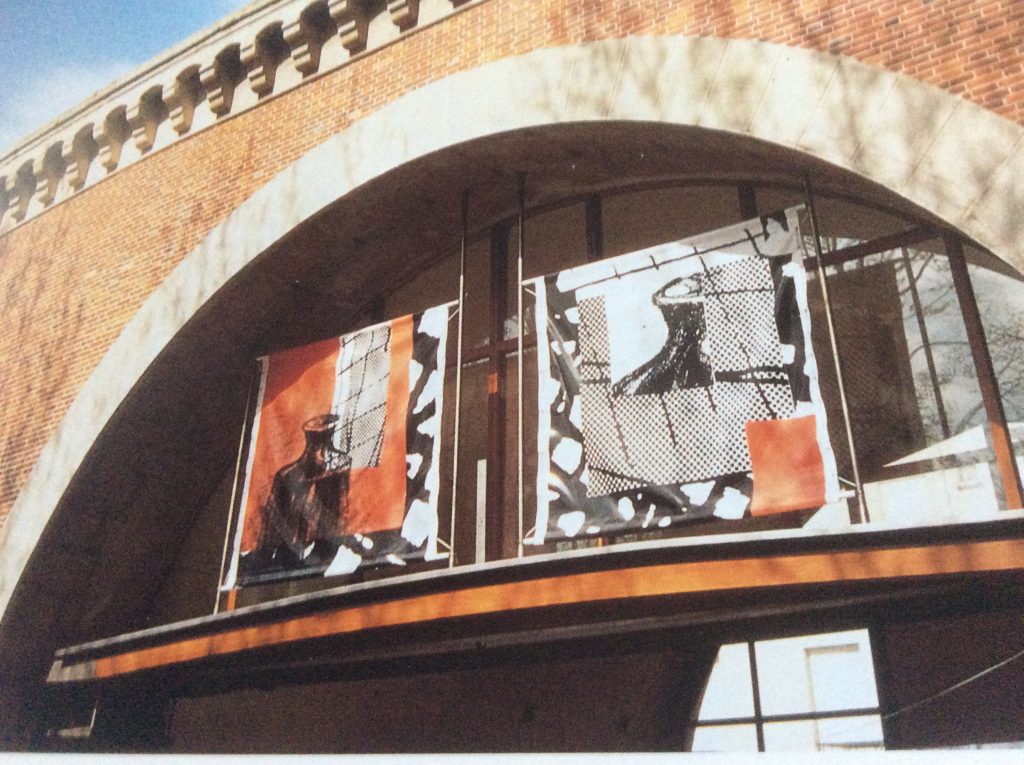

The tradition of furniture making survives in the 12th arrondissement today, in the shapes and names of thoroughfares and courtyards which still have echoes of the life that used to exist. There are a small number of on-street workshops, and you can find handmade pieces – and striking design – in the elegant galleries of the Viaduc des Arts, (below) located in the arches carrying the old railway line from Bastille to Vincennes.

Your love for and familiarity with the setting you recreate for your characters in Heartwood makes the behaviour and actions of the people in the story completely authentic and therefore memorable. The city of Paris is itself a significant actor in the book.

Thank you Lorraine. I think that trying to catch the character of Paris as it changed over the decades – a little like trying to grasp at memory – was really important to me in writing the book. ‘Homage’ to a place which was never my home.